LSU Research Bites: How Termites With the Same DNA Resize Their Brains for Different Roles

January 26, 2026

The Formosan subterranean termite, AKA the super-termite, is notorious in Louisiana. It is invasive and the nightmare of homeowners. Both its colonies and its destructive potential are large. Yet, we might not give termites enough credit for how well they work together — and how well their brains are designed for it.

Brain tissue is energetically expensive. Our human brains comprise only about 2% of our body mass, yet they consistently consume 20% of our metabolic energy. So how do insects that live in complex, role-based colonies, like bees and termites, balance cognitive and energy demands in such small bodies?

LSU researchers set out to answer this question for termites, whose tiny brains must somehow fulfill the functions of different castes: workers that build, forage, and feed; soldiers that protect; swarmers that disperse and seek mates; and reproductive queens and kings.

Compared to other social insects like bees, little is known about how termites develop such a variety of roles.

“We wanted to investigate if olfactory and visual capabilities vary among the different castes of the Formosan subterranean termite,” said Paula Castillo, a PhD graduate of the LSU AgCenter and now an extension associate at the AgCenter and the USDA Honey Bee Lab.

Paula Castillo

Castillo suspected that because different termite castes have distinct behaviors and sensory requirements, their brains may develop differently. Workers are eyeless but need strong olfactory senses to track down food, while reproductive swarmers need to see well to fly and find mates.

Yet all termites in the colony are born the same, from almost genetically identical eggs. If their brains do end up very different by caste, how is this possible, and what triggers the changes?

In a study published in Royal Society Open Science, Castillo and Qian Sun, an assistant professor of entomology at the AgCenter, used fluorescent confocal microscopy to examine the brains of termites.

They found that the size and morphology of a termite’s brain vary between castes, triggered by environmental and colony role changes. Winged swarmers had by far the largest brains—twice the size of the other castes' brains—to support their brief but complex above-ground life. They also had wider brains with well-developed optic lobes. These optic lobes were mostly lost in queens and kings, who hang out underground and thus trade energetically costly light-sensing brain cells for larger reproductive organs.

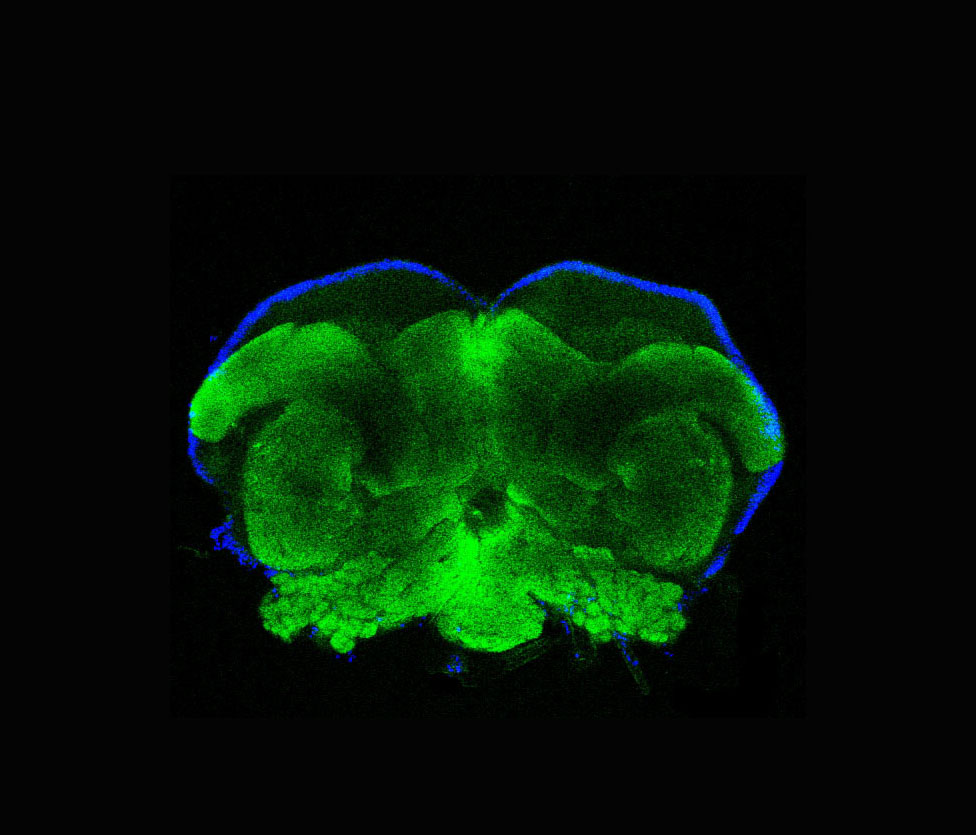

The head of a worker termite, top, and the corresponding brain below it.

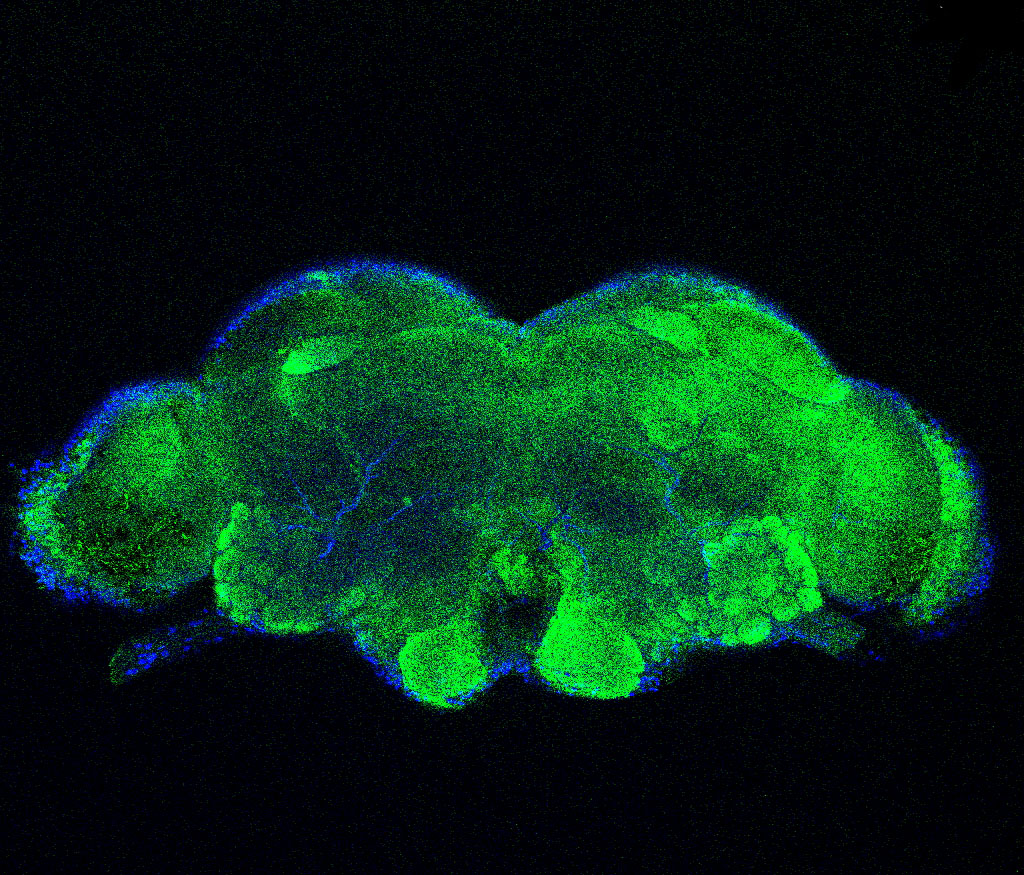

The head of a female alate termite, top, and the corresponding brain below it.

On the other hand, workers had the largest antennal lobes, responsible for the termite’s sense of smell, and soldiers had the smallest.

This study represents the first published research to compare brain structures across all castes of the Formosan subterranean termite, including immature nymphs. It is an important step forward in understanding termite social behavior and brain organization.

It shows that, like bees, termites independently developed a high degree of brain plasticity, or the ability to mold their brains to meet the sensory demands of their castes' specialized tasks.

Could studying termites even tell us something about our own brains?

“Human brains are also highly plastic, especially at early ages,” Castillo said. “Thus, even though humans and termites are very distant in evolutionary terms, preserved mechanisms can be found across species.”

The LSU Advanced Microscopy and Analytical Core provided access to the confocal microscope, where the fluorescent images for this study were taken. LSU provided an Economic Development Assistantship to Paula Castillo to support her with her Ph.D. studies.

Read the paper: Caste- and stage-dependent sensory brain plasticity in a subterranean termite

Next Step

Discover stories showcasing LSU’s academic excellence, innovation, culture, and impact across Louisiana.