The Quiet, Multi-Million-Dollar Song from the Sea

LSU researchers in multiple colleges and units are paying close attention to the bivalve some call “the canary in the ocean”—the luscious and delicate oyster. Louisiana oysters can teach us a lot about the environment and form the foundation of an $84 million industry.

A not-so-dirty dozen of LSU oyster researchers: Clockwise from the lemon: Carolyn

Ware (English), Crystal Johnson (Environmental Sciences), Morgan Kelly (Biological

Sciences), Brian Callam (Louisiana Sea Grant Oyster Research Lab), Zack Godshall (English),

Megan La Peyre (Renewable Natural Resources), Jerome La Peyre (Animal Sciences), Dr.

James Diaz (Public Health, Medicine), Don Davis (Louisiana Sea Grant), Michael Pasquier

(Religious Studies, History), Zhiqiang Deng (Civil and Environmental Engineering),

James Catano (English), and Steve Pollock (LSU Innovation Park).

LSU AgCenter

You sometimes hear the expression “undergoing a sea change.” It’s possible oysters

made it up. Few living organisms (other than corals) are more vulnerable to their

surroundings. This is because they’re stationary and cannot swim away when storms

approach, oil slicks stretch overhead, low tides hoist them into the air, or waters

approach a simmer (or suddenly stop being salty). Instead, oysters die.

But not without a fight. While an open oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water

each day—it’s a skilled sea-keeper (if that’s what the ocean’s housekeepers are called)—stressed

oysters can close up for protection. They cannot eat or breathe while they bide their

time in isolation, so it’s not particularly good for them in the long run, but LSU

research has shown that Louisiana oysters have developed survival skills that Texas

oysters, for example, do not have.

“The oyster is part of the fabric of Louisiana. It is one of the most important species in our estuary, providing critical habitat to other marine life, and helping to clean the water through its filter-feeding activities. The applied research occurring at the Oyster Research Laboratory on Grand Isle shows LSU’s long-standing dedication to the sustainability and advancement of the Louisiana oyster resource and the largest commercial oyster industry in the United States.”—Patrick D. Banks, Assistant Secretary, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries

Below, you’ll learn about some of the work LSU scholars are doing to protect oysters

and the oyster industry in a constantly changing environment, make raw oysters safer

to eat, and document “oyster people” and the deep cultural impact oyster farming has

had on life in Louisiana for centuries.

It’s the Rock and the Hard Place: Oyster Life and Death

About a third of all U.S. oyster landings come from Louisiana, and the state continues

to produce the most oysters for raw consumption. But production has seen sharp dips,

such as after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010,

and the openings of the Bonnet Carré Spillway for flood control in 2018 and 2019.

Morgan Kelly, associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, Jerome

La Peyre, professor in the School of Animal Sciences, and Megan La Peyre, adjunct

professor in the School of Renewable Natural Resources, are studying how oysters behave

under stress: how they grow, live, and die—the ultimate, but also often first, victims

of circumstance.

As the state orchestrates freshwater diversions and uses the Mississippi River—carrying

millions of tons of sediment—as a land builder to combat coastal land loss, water

salinity in the estuaries where oysters thrive can fluctuate wildly.

Like corals, oysters create three-dimensional structures, or reefs, where juvenile fish can hide. Many of the types of fish in the Gulf of Mexico that are commercially or recreationally important get their start in oyster reefs.

“Freshwater, especially when combined with warm temperatures, can be very stressful

for oysters who prefer a mix of salty and sweet,” Kelly said. “What we try to do is

understand how this impacts oysters physiologically.”

The researchers have compared Louisiana oysters to Texas oysters as well as bivalves

from New Brunswick, Canada. What they’ve found is that oysters are better at adapting

to changes in their own environment than elsewhere, and don’t necessarily do well

when moved. Louisiana oysters can withstand more freshwater than Texas oysters while

the Canadian ones seem better at surviving large fluctuations in temperature (very

cold, very warm).

Morgan Kelly identifies strains of oysters that can survive in low-saline conditions at the Michael C. Voisin Oyster Hatchery and Louisiana Sea Grant Oyster Research Lab in Grand Isle, Louisiana.

LSU

“This means that, when we think about doing restoration projects after natural or

man-made disasters and try to restore oyster reefs, we really need to pay attention

to where the parent stocks of oysters come from,” Kelly said.

Oysters are an important source of habitat for other species as well. Like corals,

oysters create three-dimensional structures, or reefs, where juvenile fish can hide.

Many of the types of fish in the Gulf of Mexico that are commercially or recreationally

important get their start in oyster reefs. Also, the physical barriers oysters build

over time can protect shorelines and marshes by counteracting waves during powerful

storms and surges.

To understand what is happening to oysters “underneath the hood”—what is stressing

them out and why they sometimes die—Kelly studies oyster gene expression in her lab.

Inside every living cell (human or animal), as the organism is trying to respond to

a stressor, the first thing that happens is that a copy of a particular part of the

organism’s DNA is made—the instructions for how to make a specific protein. (In the

body, proteins drive growth and change.)

“You can liken this to jotting down a recipe on a Post-It note before heading into

the kitchen,” Kelly said. “Cells are full of Post-It notes like this, and by sequencing

millions of them and reading them, we can learn what an organism is getting ready

to do—whether that’s to grow, or fight a disease, or respond to heat stress. Through

gene expression, we’re letting the oysters tell us what’s going on. Without this work,

a dead oyster would just be a dead oyster, while we’re trying to explain why.”

Much of the researchers’ work over the years has received support and funding through Louisiana

Sea Grant.

Oysters on Land: Toward a Sustainable, Climate-Proof Industry

Steve Pollock has the radio on really loud inside his “bunker” at LSU Innovation Park.

It’s meant to scare off squirrels who otherwise rip insulation off the building. Inside,

there are four 5,000-gallon tanks that hold tiny baby oysters, which the squirrels—luckily—don’t

care much about.

After teaching biology at LSU for 11 years, Pollock got into the oyster business.

He started a farm at his camp in Grand Isle on Caminada Bay in 2015. He then added

an oyster nursery in 2017 to grow oyster seed for himself and other farms, and finally

a hatchery in 2018. After his camp flooded five times and he became more familiar

with some of the new off-bottom farms where “boutique” oysters are grown in baskets

on lines where predators cannot get to them and there is more oxygen and potentially

less contaminants in the water (and unlike reefs, baskets can be moved from one area

to another), Pollock got an idea. What if he could farm oysters on land, in tanks?

Now, cimate change, extreme weather, and flooding are no longer sources of frustration

and possible financial ruin for Pollock. He has complete control over the water level,

temperature, acidity, and salinity (it’s an efficient recycling system) and he’s getting

closer to controlling the water composition as well.

As with most start-ups, there have been challenges. Something was eating Pollock’s

oyster larvae, and it took him a few months to figure out what it was—vibrios, or

bacteria. Not the kind that makes people sick, but definitely the kind that gobbles

oyster larvae. As he took adult oysters from the coast to procreate in his tanks,

the oysters brought naturally occurring bacteria with them. Vibrios are a common nuisance

for aquatic farms, nurseries, and hatcheries everywhere.

“Our ultimate goal is to supply off-bottom culture farms and help out with coastal

restoration projects,” Pollock said. “Although I’m now doing this on land, I started

because I love the Louisiana coast and love being on the water—and the good news is,

whenever I go down to the camp, it still counts as a business trip.”

Marine microalgae are an important food source for the oyster larvae growning at the Michael C. Voisin Oyster Hatchery. This continuous algal production system can produce up to 2,000 liters (~530 gallons) of feed daily and the different colored lights have different wavelengths to help with photosynthesis. “Plus it's fun, especially at night,” said director Brian Callam.

LSU AgCenter

“We want to develop oysters that are better adapted for the local conditions we have as well as future changes we anticipate.”—Brian Callam, director of the Michael C. Voisin Oyster Hatchery and Louisiana Sea Grant Oyster Research Lab

A mile from Pollock’s camp in Grand Isle, two miles up the road, lies the Michael

C. Voisin Oyster Hatchery and Louisiana Sea Grant Oyster Research Lab, a collaboration

between LSU and the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries to help restore

oyster populations and public seed grounds. Their new building, in use since 2015,

was partly funded by BP as compensation after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and

is rated to withstand the strongest of hurricanes (category five), with generators

capable of operating for at least a week with no one present. The director, Brian

Callam, whose Twitter tagline is “bikes, banjos, bivalves,” leads a series of applied

research projects on husbandry techniques, gear development, and breeding work.

“We want our work to have as an immediate impact as we can,” Callam said. “We want

to develop oysters that are better adapted for the local conditions we have as well

as future changes we anticipate, such as more freshwater, so we can help protect the

industry and keep our oyster populations going.”

He’s worked closely with Pollock, applauds his progress, and appreciates the big technological

challenges that come with the artificial creation of seawater on land.

“Oyster larvae are incredibly sensitive to everything,” Callam said. “It’s actually

one of the test species scientists use to find out if something is toxic. You just

dump in a bunch of oyster larvae and see if they die. So, doing oysters on land is

definitely not easy, but it’s the way forward, for sure.”

On at least a weekly basis, Callam interacts with oyster farmers to share research

results and discuss newly developed technologies. Some of those farmers are just starting

out, having never worked the water before, while others are fourth- or fifth-generation

and still farming the way the first or second did.

“Working with the farmers is the most exciting and rewarding part of my work,” Callam

said. “The hardest part is having a research farm where I want to eat all of the research

animals.”

Space Shuckin’: Making Oysters Safer to Eat, With Help From NASA

Crystal Johnson, associate professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences in

the LSU College of the Coast & Environment, knows a bacterium doesn’t care where it

gets its food—whether the ocean, an oyster, or the human mouth. She studies how microbes

respond to their environment, including vibrios, which play an important role in nature’s

clean-up system. They break down organic matter in all aquatic environments—lakes,

rivers, marches, and the sea—help recycle carbon, and degrade waste. Vibrios are everywhere.

“What’s exciting and frustrating at the same time is that 99 percent of these vibrios

are not pathogenic or harmful; they’re not going to make people sick; their goal is

not to make us sick,” Johnson said. “So, if you go to the ocean, you’re likely not

going to have your arm or leg amputated with 24 hours from a tiny cut—but it does

happen in rare cases, and that’s what we’re trying to prevent.”

... a multidisciplinary team is going to combine satellite images and artificial intelligence-based modeling to predict where dangerous levels of vibrios might be present.

Vibrios have a less appealing name, too—flesh-eating bacteria—and we’ve all heard

horror stories. Since 2018, about 500 people along the Gulf Coast have died from vibrio

infection, with many others losing limbs. Now, eating raw oysters isn’t often (if

ever) the reason for losing an arm or leg; those disastrous vibrio infections usually

stem from an open wound or sore, such as a cut, scrape, puncture, or bite. And yet,

for lovers of raw seafood, oysters remain the most dangerous thing to eat.

Crystal Johnson in her kayak.

Photo by Jane Patterson

Johnson is now part of a large project funded by NASA and the Louisiana Board of Regents to make raw oysters safer to eat. Led by Zhiqiang Deng, a professor in the Department

of Civil and Environmental Engineering, a multidisciplinary team is going to combine

satellite images and artificial intelligence-based modeling to predict where dangerous

levels of vibrios might be present. Johnson will be out on the boat or in her kayak

taking measurements (temperature, salinity) and collecting water samples to confirm

the team’s predictions.

“This is a problem we’ve been trying to tackle for a really long time,” Johnson said.

“Vibrios are related to temperature, so the warmer the waters get, the more vibrios

you’ll see. The best way to protect human health is to predict the conditions where

vibrios are going to be in high concentrations at potentially dangerous levels. After

all, you can’t just go treat the Gulf of Mexico with penicillin.”

Another collaborator on the NASA and Board of Regents project is Dr. James Diaz, professor

in the LSU School of Public Health and the LSU Health Sciences Center School of Medicine

in New Orleans. He brings expertise in environmentally associated diseases and poisonings,

particularly those that are food- and waterborne, as well as on impacts of climate

change on public health.

Incidentally, speaking of making oysters safer to eat, the patented AmeriPure Process,

which uses heat and cold shock to significantly reduce harmful bacteria to make oysters

safer for raw consumption year-round and not only in the “r” months, was developed

by LSU researchers Sam Grodner and Douglas Park in the 1990s. Louisiana oysterman

John Tesvich (see below), among others, uses this process.

Oyster Products: Innovative Ideas

Subramaniam Sathivel, professor of food engineering in the LSU AgCenter, has worked

with Louisiana oyster businesses, such as Motivatit Seafoods in Houma, Louisiana,

on new techniques to freeze and package oysters and oyster products. One of those

projects involved turning oysters too small to sell as-is (so-called popcorn oysters)

into oyster powder to flavor soups and stews, including gumbo. This idea received

support from the LSU Board of Supervisors in 2018 through the LIFT program.

Oyster People: Resilience and Change

Carolyn Ware, folklorist and associate professor in the Department of English, started

going down to the fishing camps and oyster boats in Plaquemines Parish after the New

Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation asked her to find new people who could demonstrate

their craft in the Louisiana Folklife Tent at Jazz Fest in 1994.

“I was thinking, I’ll get someone to come and sit and work on this net or whatever,

but each source led to another,” Ware said. “I ended up falling in love with the culture

and the people, and the research made me see Louisiana cultures altogether differently.

Before then, I had paid little scholarly attention to sense of place and the connections

people have to land and waterscapes. I learned a lot and it became very personal to

me, how important oystering is to these people and the state.”

One of the first things that struck Ware was how the people she met considered themselves

farmers, not fishermen. How they tended their oyster beds—set in rock on the water

bottoms—as their fields, generation after generation.

An oyster truck makes a delivery in the French Quarter.

State Library of Louisiana

“They’re not just going out on their boats and scooping up oysters,” Ware said. “They tend their fields all year, and oyster season sets the pace and the schedule; when to do this or that, maybe have a big celebration. ‘This is when we start cleaning up our oyster grounds; this is when we start putting new oysters in…’ In their view, they improve the waterways with their work.”

“These are family farms and there’s a sense of legacy and responsibility (...) It’s an investment that’s not just economic.”—Carolyn Ware

The second thing that struck Ware was how almost all of the “oyster people” she met were Croatian or Croatian descendants. (This is still the case today—the Louisiana Oyster Task Force, for example, led by Mitch Jurisich, includes voting members such as Sam Slavich, Jakov Jurisic, John Tesvich, and Peter Vujnovich, Jr.) While Croatians continue to dominate the oyster industry in Louisiana, most who immigrated here never touched an oyster back in Croatia—but it’s a maritime culture, across the Adriatic Sea from Italy, and many translated their European experience with mussels and fish when they came to America. Plus, they had compatriots here to teach them.

“They have a deep, experience-based knowledge of the water bottoms they work,” Ware

said. “Generations have poured all of their resources into the particular areas they

lease and they’re very protective of them. These are family farms and there’s a sense

of legacy and responsibility.”

“It’s an investment that’s not just economic,” Ware continued. “The land they work

ties them to who they are and their memories of family and community members who taught

them. For more than a century, Croatian oystermen have been close observers of land

loss, salinity changes, and other impacts on Louisiana’s wetlands. And they have been

strong advocates for these places.”

Ware is currently working on a book manuscript on the folklife of different ethnic

groups in Plaquemines Parish where oystering, of course, figures prominently. Ever

since Hurricane Katrina in 2005, there has been great worry both inside and outside

the oyster community of this iconic culture possibly “washing away.” This led Ware

to introduce a fellow LSU English professor, James Catano, to some of her oyster contacts.

Over a period of about five years, they went down to Plaquemines Parish together with

students to document the life of the oystering community. This resulted in a film,

An Enduring Legacy: Louisiana’s Croatian-Americans, about grit, determination, and the survival of true made-in-Louisiana culture (featuring,

among others, John Tesvich and Pete Vujnovich).

It is hard to stomach losing your farm, your livelihood, and legacy in the short term, even when it’s for the greater good in the long run.

“It was important to me to raise awareness about these people and their struggles

in recovering after Hurricane Katrina, and later, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill,”

Catano said. “Their story teaches us about the wonderful diversity this state has

had over its entire history and how it has built up the strength of our culture and

economy. It teaches us about resilience in the face of tremendous challenges and about

the history of immigration in Louisiana; the successes and contributions of immigrants

to our country.”

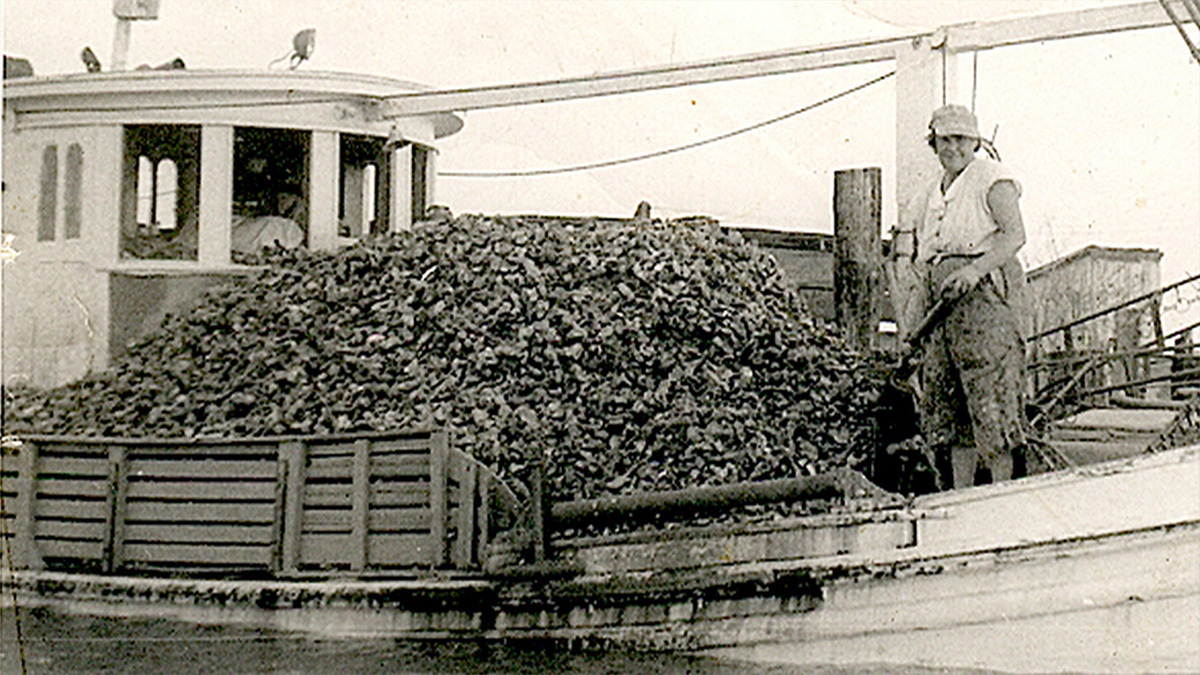

Neda Jurisich was born and raised in Croatia but married a Croatian oysterman who settled in Louisiana. She often had to work on the family boat. According to LSU researcher Carolyn Ware, Jurisich was a force of nature—Ware wrote about her and three generations of Croatian Louisiana women in a book called Louisiana Women, Vol. 2.

Photo courtesy of the researchers

Another LSU scholar who has documented the important role oysters play for people

in Louisiana’s coastal communities—and not just Croatians and Croatian descendants—is

Michael Pasquier, associate professor of religious studies and history and the Jaak

Seynaeve Professor of Christian Studies. He produces a podcast called Coastal Voices and created a documentary, Water Like Stone, with Zack Godshall, a filmmaker and assistant professor of English at LSU. In Pasquier’s

mind, oystering can help tell a story of how people adapt to changing environments

and the resilience of cultures and communities at large.

Another document of the oft-precarious life on the coast is Louisiana Sea Grant scholar

Don Davis’ 2010 book, Washed Away? The Invisible Peoples of Louisiana’s Wetlands. Here he noted how hurricanes like Katrina, Rita, Gustav, and Ike brought many of

the state’s sea-level citizens into the public light and revealed deep, ancestral

connections to land that is sinking, eroding, and disappearing into the sea.

Meanwhile, important coastal fishing and farming industries, such as oystering, face

a double threat in that potential solutions to long-term land loss—such as freshwater

diversions, which use sediment- and nutrient-rich water as a land builder—can have

immediate consequences for fish and seafood. For sensitive oysters, freshwater diversions

are particularly problematic because oysters cannot move on to more saline areas and

also because paid oyster leases—the legal and exclusive rights to farm and harvest

oysters and build up productive oyster beds, sometimes over generations—are tied to

specific geographic areas. It is hard to stomach losing your farm, your livelihood,

and legacy in the short term, even when it’s for the greater good in the long run.

By altering where the productive habitats are, freshwater diversions are bound to

create winners and losers—and for oysters and oyster farmers, changes in the water

are felt directly.

Elsa Hahne

LSU Office of Research & Economic Development

ehahne@lsu.edu