The Delta Breathes: Mapping Carbon Along the Muddy Mississippi

October 01, 2021

By Christine Wendling

(Originally featured in LSU Research Magazine)

Rivers and deltas can release significant amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, which contributes to global warming. But until recently, climate modelers have had limited information on this process. A team of LSU scientists, in collaboration with Southern University, have accepted the challenge of analyzing this complex carbon export in the largest delta in the United States—the Mississippi River Delta.

Carbon is the fourth most abundant element in the universe and the foundation for all life on our planet. It is cycled and recycled through land, sea, and atmosphere in a process scientists call carbon cycling. To many, this process might look as though the Earth is breathing. And if the Earth breathes, then surely river deltas, with their bronchial-like river branches, channels, and flow-through lakes and estuaries, are like lungs that inhale the carbon into their waters, rocks, plants, soil, and fossil fuels and sometimes exhale it into the atmosphere—in the form of carbon dioxide, or CO2, a greenhouse gas that contributes to global warming.

The LSU team is led by Associate Professor Zuo “George” Xue and comprises three additional faculty members from the College of the Coast & Environment: Professor Eurico D’Sa, Associate Professor Kanchan Maiti, and Associate Professor Victor Rivera-Monroy, along with several graduate students. They are tracking the carbon as it moves through the Mississippi River Delta and the Gulf of Mexico coast to see how it affects coastal water quality. In conjunction, the Southern University team—led by Zhu Hua Ning, a professor of forest ecophysiology and tree anatomy—is studying the terrestrial carbon export.

Photo of the first LSU/Southern joint wetland field work at Wax Lake Delta. From left to right: Ivan A Vargas Lopez, LSU graduate student; Victor Rivera-Monroy, LSU PI; Hande Kilic, Southern graduate student; Le Zhang, LSU graduate student; and Zuo “George” Xue, LSU PI.

– George Xue

“We are excited to collaborate with Southern University. Southern is the largest Historically Black College & University, or HBCU, in Louisiana and five of our six graduate students are minorities and five are women,” Xue said, “My co-PI, Victor Rivera-Monroy is working closely with Southern faculty and students in the field, often for their very first time. He is also teaching the students how to analyze soil samples here in the College of the Coast & Environment’s wetland lab,” Xue said.

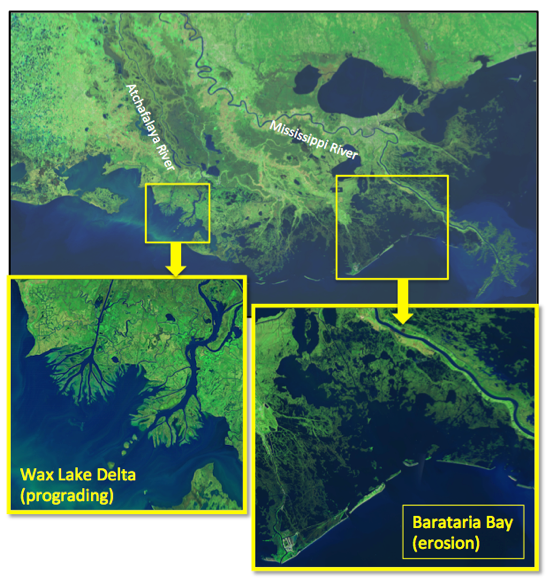

Together, the teams are exploring two contrasting sites in the Mississippi River Delta plain: Barataria Bay, which has a coastline that is experiencing significant subsidence and land loss, and Wax Lake Delta, a fast-growing delta that is expanding. When soil from a delta submerges into the coastal ocean—due to land loss, for example—carbon is released from the soil’s organic matter. This greenhouse gas may become trapped when the aquatic environment acts as a carbon sink or is released into the air. While the Gulf of Mexico generally acts as a carbon sink, as do mid-to-high latitude oceans worldwide, the coastal zone of Louisiana can become oversaturated with CO2, releasing carbon into the atmosphere and exacerbating climate change.

To explore how carbon is exported from delta-dominated systems to the coastal ocean, LSU and Southern in partnership with the Louisiana Space Grant Consortium were awarded a $1.5 million Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research, or EPSCoR, grant from NASA and the Louisiana Board of Regents in 2018.

Now, in year two of the three-year project, they have collected hundreds of water and soil samples and completed six offshore cruises, led by Maiti, and seven wetland surveys, led by Rivera-Monroy, covering an area of 3,200 square miles along the coastal zone of the northern Gulf of Mexico.

“This EPSCoR project is providing Louisiana with a lot of research infrastructure. For example, over the past two years, we purchased state-of-the-art carbon dioxide measuring equipment for Louisiana research, and now we have created our own cutting-edge carbon model that is specific to our own delta. With it, we will be able to answer so many questions in the future,” Xue said.

Mississippi River Delta Plain showing regional study sites: Left: prograding Wax Lake Delta; Right: Barataria Bay (acute erosional process, land loss). Satellite data source: USGS Landsat.

– George Xue

This new circulation model was built to encompass the Gulf of Mexico, Barataria Bay, and Wax Lake Delta. With the data collected, they have already performed an accurate hindcast for the Gulf of Mexico covering the past three decades. Now, Xue says the next step is to incorporate climate change scenarios into the model to provide a projection of the future condition.

“With this newly constructed model, combined with global climate model data from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, we can have an assessment of the carbon export for both current and future conditions. We aren’t quite there yet. But, we are heading there,” Xue said.

Soon they will have collected enough data to produce a carbon “budget” for the Mississippi River Delta by comparing the site that is losing land with the site that is building land and assessing the net carbon being exported into the ocean and atmosphere. This information is especially valuable because carbon budgets apply a dollar amount to emissions that enter the atmosphere and can be used to generate tax credits for businesses, incentivizing them to reduce their carbon emissions. For example, California has an economy-wide cap-and-trade system, and the northeastern U.S. uses a carbon pricing program known as the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. These incentives may one day expand into Louisiana as well. Furthermore, this modeling platform will become part of a toolbox that can be shared freely with any scientist and adapted for use in modelling deltas and estuaries around the globe.

“I am fortunate to be leading and managing this project as it’s been a very good learning curve for me," Xue said. “We have issues that need to be addressed—land loss and possible ocean acidification, but we don’t know about the fate of the carbon. So, that’s something that we need to know for Louisiana.”