LSU professor combats counterfeit goods with a new identification and authentication approach

September 27, 2022

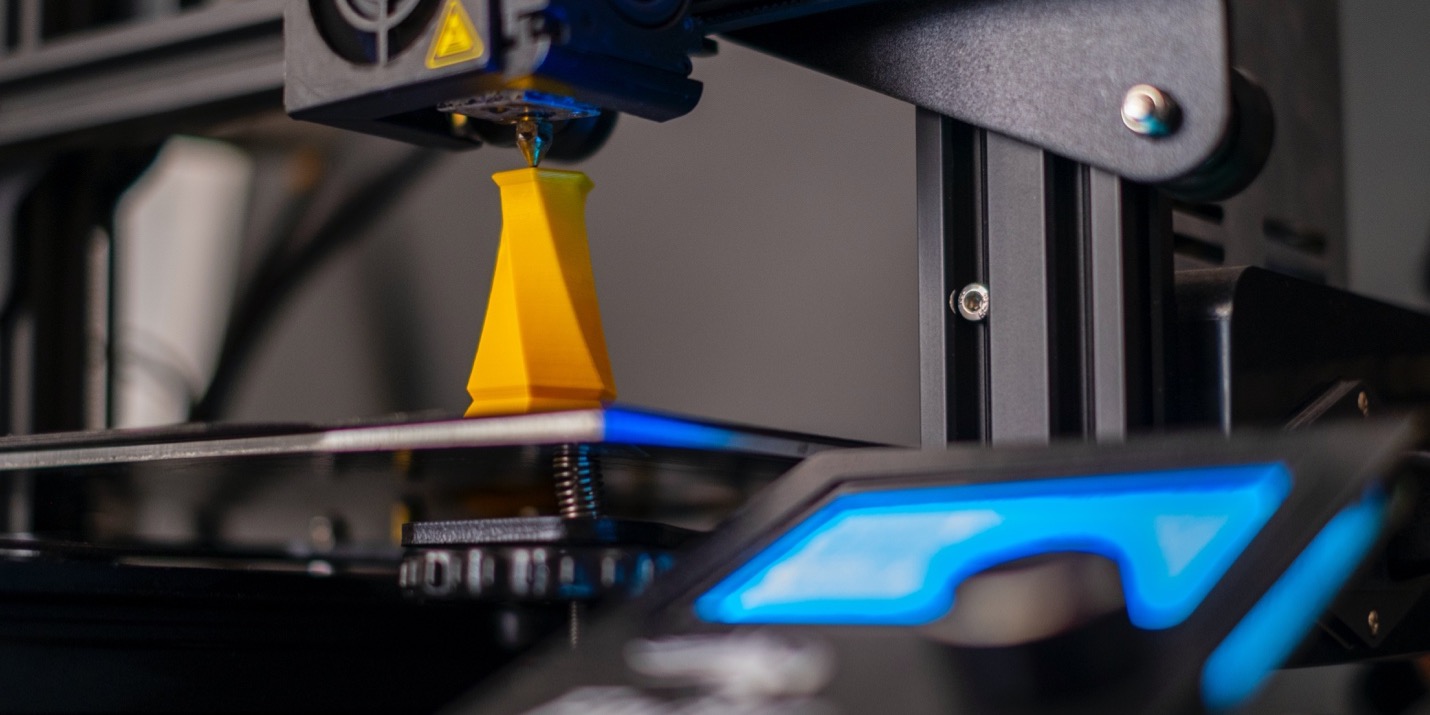

Additive manufacturing utilizes customizable technology, helping businesses streamline production processes and create end-use parts.

– Photo by: Osman Talha Dikyar on Unsplash

BATON ROUGE - Disruptions to the supply chain can impact all manufacturing aspects and result in a stalling of factory production. Something as small as a missing part is more than enough to create havoc in supply chain logistics and ultimately lead to the shutdown of operations.

To avoid an increasingly fragile global supply chain, companies are investing in additive manufacturing (AM), including 3D printing or rapid prototyping. Additive manufacturing utilizes customizable technology, helping businesses streamline production processes and create end-use parts, reducing fabrication time and costs. However, this cost-saving and efficient manufacturing method comes with significant risks.

“At additive manufacturing tradeshows, we often hear the phrase ‘anyone can make anything.’ However, change one word in that phrase to ‘anyone can counterfeit anything,’ and it takes on an entirely different meaning.”

Professor Les Butler, LSU Department of Chemistry

Many parts used to build our homes, vehicles, and electronics are mass-produced and purchased by manufacturers in large quantities. These parts are held to stringent manufacturing guidelines to ensure part quality and consumer safety.

However, as the AM industry grows, companies find it harder to control their intellectual property. As a result, when counterfeit parts enter the market, they generate health and safety risks, reduced product reliability, legal implications, and economic impacts.

According to LSU Chemistry Professor Les Butler, counterfeit parts, such as automotive spark plugs and timing belts, enter the supply chain before they hit the shelves in brick-and-mortar auto part stores. These fake components can lead to catastrophic automobile engine failures, endangering public safety.

LSU Chemistry Professor Les Butler's family-owned garage and auto part store in Yankeetown, Fl (1974).

Growing up working at his father’s gas station/mechanic shop/hardware store, Butler developed a deeply rooted commitment to uncompromising hardware quality. He is on a mission to secure the supply chain and pump the brakes on counterfeit products.

In a recently funded Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Phase I award from the U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Butler is developing an enhanced anti-counterfeiting measure protecting AM parts.

Refined Imaging, a company co-owned by Butler and based in Baton Rouge, is developing a system to protect against counterfeit manufactured components, such as automotive and aerospace parts, by connecting a physical part with a secure database safeguarded by blockchain technology.

The company and its partner, SIMBA Chain, place a cyber-physical trust anchor in a component during the AM process through selective porosity, a process of removing selective constituents of a material. The void space within the part creates encoded digital information that will not affect the structure's integrity and is undetectable with visual and conventional X-ray inspections.

With X-ray interferometry, the voids are imaged, and the data is entered into a secure database protected by blockchain technology. Blockchain, a digital ledger of transactions duplicated and distributed across a network of computers, will allow manufacturers to record information that cannot be altered or deleted. For proof of authentication, the imaging process is repeated, and data is compared to a blockchain data file. Inspectors will then receive a yes/no response for component authentication.

Blockchain systems can also be applied to smart contracts. Unlike regular contracts, smart contracts utilize blockchain technology in real-time, ensuring compliance from all users involved. For instance, a repair shop using AM will have a smart contract to the blockchain to log a new AM part as it is printed and the provenance of the part as it is warehoused, shipped, inspected, and at end-of-life.

“Our goal is to secure the AM supply chain from part print to part end-of-life, without change to part design and production workflow commensurate with the security needs for that part,” Butler said. “By leveraging blockchain technology to improve supply chain safety issues, companies will be able to protect intellectual property and public safety.”

Professor Les Butler’s research at LSU focuses on developing new X-ray and neutron methods for applications in the chemical, material, and plant sciences. To learn more about X-ray interferometry, visit his research page.