How does the duration of plant flowering give us insight into the effects of climate change?

LSU researcher collects data using citizen-science app, iNaturalist

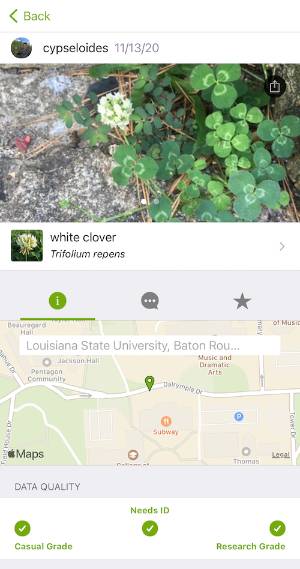

A user-submitted observation on LSU's campus on the iNaturalist app.

Photo Credit: iNaturalist

In a newly published paper, one LSU researcher sought the help of citizen scientists across the country to better understand the effects that geographical locations coupled with climate changes have had on plants that flower.

Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences Daijiang Li and his colleagues at the University of Florida in Gainesville mined hundreds of thousands of data entries submitted by nature enthusiasts around the U.S. between 2017 and 2019 to iNaturalist, one of the world’s most popular social networking apps for sharing biodiversity information. This app-based initiative of the California Academy of Sciences and National Geographic allows anyone with an internet connection to upload location-coded images and sounds of plants and animals.

In their paper, “Climate, Urbanization, and Species Traits Interactively Drive Flowering Duration,” the researchers investigated potential climate and landscape drivers of the beginning, ending, and duration of flowering of 52 plant species with varying key characteristics.

Understanding the patterns that occur is critical for predicting the effects of future climate and land-use change on plants, pollinators, and herbivores, according to Li.

“We know the starting period of flowering relatively well, but we started to question, ‘What about the ending?’” Li said. “Understanding the duration of flowering is important to know because it can show problems (associated) with global warming.

“For example, warmer weather generally means earlier flowering. What if flowering is also ending earlier, maintaining or even trimming the flowering period? That can be risky for plants especially if their pollinators are not responding in the same way. The problem is that we don’t know much about termination and duration of flowering.”

By utilizing more than 270,000 community-science photographs, the group confirmed that longer flowering durations generally occur in warmer areas. Additionally, they also discovered that higher human population density and higher annual precipitation are associated with delayed flowering ending and extended flowering duration.

“Though this study was on various species, this can be useful information for agricultural crops,” Li said. “Thinking of the future, if the climate is getting warmer, then a farm, say, in the northern U.S. will have early flowering crops. What if pollinators are not there yet? That’s a problem. But on the other hand, if the flowering duration is longer and pollinators may have time to catch up, that could potentially reduce economic loss.

“By looking at this information, we can formulate a plan for what our response could look like in the future.”