OER Licensing

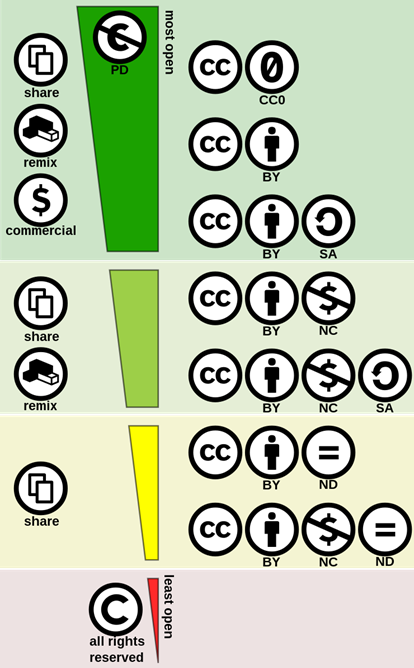

Most OER are released under Creative Commons (CC) licenses, which explicitly allow for uses beyond those typically allowed under copyright law.

Many materials are available free of cost online. However, being free of cost does not necessarily mean something is an OER. For something to be considered an OER it needs to be freely and legally allowed to be redistributed and shared.

An easy way to evaluate if something is an OER is to determine the copyright status of an item. Is it in the public domain, does it have a creative commons (cc) license or does it have a free software license (e.g., GNU license, MIT license)? If the material does not fall into one of these categories, it probably is not an OER.

The Four Components of Creative Commons Licenses

- Attribution (BY) Proper attribution must be given to the original creator of the work whenever a portion of their work is reused or adapted. This includes a link to the original work, information about the author, and information about the original work’s license.

- Share-Alike (SA) Iterations of the original work must be made available under the same license terms.

- Non-Commercial (NC) The work cannot be sold at a profit or used for commercial means such as for-profit advertising. Copies of the work can be purchased in print and given away or sold at cost.

- No Derivatives (ND) The work cannot be altered or “remixed.” Only identical copies of the work can be redistributed without additional permission from the creator.

- Machine readable

- Human readable

- Legal code

- The legal code is the base layer. This contains the “lawyer-readable” terms and conditions that are legally enforceable in court. Take a minute and scan through the legal code of CC BY to see how it is structured. Can you find where the attribution requirements are listed?

- The commons deeds are the most well-known layer of the licenses. These are the web pages that lay out the key license terms in so-called “human-readable” terms. The deeds are not legally enforceable but instead summarize the legal code. Take some time to explore the deeds for CC BY and CC BY-NC-ND and identify how they differ. Can you find the links to the legal code from each deed?

- The final layer of the license design recognizes that software plays a critical role in the creation, copying, discovery, and distribution of works. To make it easy for websites and web services to know when a work is available under a Creative Commons license, we provide a “machine readable” version of the license—a summary of the key freedoms granted and obligations imposed written into a format that applications, search engines, and other kinds of technology can understand. We developed a standardized way to describe licenses that software can understand called CC Rights Expression Language ( CC REL) to accomplish this. When this metadata is attached to CC licensed works, someone searching for a CC licensed work using a search engine (e.g., Google advanced search) can more easily discover CC licensed works.

These different license elements are symbolized by visual icons.

| Icon | Licensing Element |

|---|---|

| This symbol means Attribution or “BY.” All the licenses include this condition. | |

| This symbol means Noncommercial or “NC,” which means the work is only available to be used for noncommercial purposes. Three of the CC licenses include this restriction. | |

| This symbol means Share Alike or “SA,” which means that adaptations based on this work must be licensed under the same license. Two of the CC licenses include this condition. | |

| This symbol means NoDerivatives or “ND,” which means reusers cannot share adaptations of the work. Two of the CC licenses include this restriction. | |

| When combined, these icons represent the six CC license options. The icons are also embedded in the “license buttons,” which each represent a particular CC license type. Section 3.3 explores the combinations in detail. |

In addition to the CC license suite, CC also has two public domain tools represented by the icons below. These public domain tools are not equivalent to licenses:

| Icon | Tool |

|---|---|

|

CC0 enables creators to dedicate their works to the worldwide public domain to the greatest extent possible. Note that some jurisdictions do not allow creators to dedicate their works to the public domain, so CC0 has other legal mechanisms included to help deal with this situation where it applies. You might also see this tool being used by museums, libraries or archives. This doesn’t mean they are claiming copyright over those works, but rather they are waiving all possible rights they might have in other jurisdictions to the reproductions of those works. (More on CC0 legal mechanisms and scope in Section 3.3.). |

|

| The Public Domain Mark is a label used to mark works known to be free of all copyright restrictions. Unlike CC0, the Public Domain Mark has no legal effect when applied to a work. It serves only as a label to inform the public about the public domain status of a work and is often used by museums, libraries and archives working with very old works |

Defining the "Open" in Open Content and Open Educational Resources

The terms "open content" and "open educational resources" describe any copyrightable work (traditionally excluding software, which is described by other terms like "open source") that is either (1) in the public domain or (2) licensed in a manner that provides everyone with free and perpetual permission to engage in the 5R activities:

- Retain - make, own, and control a copy of the resource (e.g., download and keep your own copy)

- Revise - edit, adapt, and modify your copy of the resource (e.g., translate into another language)

- Remix - combine your original or revised copy of the resource with other existing material to create something new (e.g., make a mashup)Reuse - use your original, revised, or remixed copy of the resource publicly (e.g., on a website, in a presentation, in a class)

- Redistribute - share copies of your original, revised, or remixed copy of the resource with others (e.g., post a copy online or give one to a friend)

Legal Requirements and Restrictions Make Open Content and OER Less Open

While a free and perpetual grant of the 5R permissions by means of an "open license" qualifies a creative work to be described as open content or an open educational resource, many open licenses place requirements (e.g., mandating that derivative works adopt a certain license) and restrictions (e.g., prohibiting "commercial" use) on users as a condition of the grant of the 5R permissions. The inclusion of requirements and restrictions in open licenses make open content and OER less open than they would be without these requirements and restrictions.

There is disagreement in the community about which requirements and restrictions should never, sometimes, or always be included in open licenses. For example, Creative Commons, the most important provider of open licenses for content, offers licenses that prohibit commercial use. While some in the community believe there are important use cases where the noncommercial restriction is desirable, many in the community strongly criticize and eschew the noncommercial restriction.

As another example, Wikipedia, one of the most important collections of open content, requires all derivative works to adopt a specific license - CC BY SA. MIT OpenCourseWare, another of the most important collections of open content, requires all derivative works to adopt a specific license - CC BY NC SA. While each site clearly believes that the ShareAlike requirement promotes its particular use case, the requirement makes the sites' content incompatible in an esoteric way that intelligent, well-meaning people can easily miss.

Generally speaking, while the choice by open content publishers to use licenses that include requirements and restrictions can optimize their ability to accomplish their own local goals, the choice typically harms the global goals of the broader open content community.

Poor Technical Choices Make Open Content Less Open

While open licenses provide users with legal permission to engage in the 5R activities, many open content publishers make technical choices that interfere with a user's ability to engage in those same activities. The ALMS Framework provides a way of thinking about those technical choices and understanding the degree to which they enable or impede a user's ability to engage in the 5R activities permitted by open licenses. Specifically, the ALMS Framework encourages us to ask questions in four categories:

Access to Editing Tools: Is the open content published in a format that can only be revised or remixed using tools that are extremely expensive (e.g., 3DS MAX)? Is the open content published in an exotic format that can only be revised or remixed using tools that run on an obscure or discontinued platform (e.g., OS/2)? Is the open content published in a format that can be revised or remixed using tools that are freely available and run on all major platforms (e.g., OpenOffice)?

Level of Expertise Required: Is the open content published in a format that requires a significant amount

Meaningfully Editable: Is the open content published in a manner that makes its content

essentially impossible to revise or remix (e.g., a scanned image of a handwritten

document)? Is the open content published in a manner making its content easy to revise

or remix (e.g., a text file)?

Self-Sourced: It the format preferred for consuming the open content the same format preferred

for revising or remixing the open content (e.g., HTML)? Is the format preferred for

consuming the open content different from the format preferred for revising or remixing

the open content (e.g. Flash FLA vs SWF)?

Using the ALMS Framework as a guide, open content publishers can make technical choices

that enable the greatest number of people possible to engage in the 5R activities.

This is not an argument for "dumbing down" all open content to plain text. Rather

it is an invitation to open content publishers to be thoughtful in the technical choices

they make - whether they are publishing text, images, audio, video, simulations, or

other media.

Should you choose to exercise any of the 5R permissions granted under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license, your attribution must include the Title, Author, Source, and License. You might choose to use the following model attribution:

Defining the "Open" in Open Content and Open Educational Resources was written by David Wiley and published freely under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license at opencontent.org/definition.

Create your own OER License

Creative Commons licenses give everyone from individual creators to large companies and institutions a clear, standardized way to grant permission to others to use their creative work.

From the reuser’s perspective, the presence of a Creative Commons license answers the question, “What can I do with this?” and provides freedom to reuse, subject to clearly defined conditions.

All Creative Commons licenses ensure that creators retain their copyright and get credit for their work, while permitting others to copy and distribute it. Although the tools are designed to be as easy to use as possible, there are still some things to learn in order to fully understand their mechanics.

- How to add a Creative Common license to your work

- Best Practices for attribution

- The Downloads. page of Creative Commons' website may be a helpful media resource if you're creating a visual presentation, or an assignment. That page includes downloadable CC license and element icons, and more.

Best practices for attribution.

Attribution: [Abbey Elder] (2018, Jul.16) Attribution & Fair Use: Copyright in Open Education #1 [Video File]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/jGTUHdadqJU (CC-BY 4.0)