A project of the Manship School of Mass Communication, LSU

Analysis

Journalists need to understand rape culture to report on sexual abuse

By Tracy Everbach

(November 12, 2017) - “It was 40 years ago.”

“Take Joseph and Mary. Mary was a teenager and Joseph was an adult carpenter. They became parents of Jesus.”

“There’s nothing wrong with a 30-year-old single male asking a 19-year-old, a 17-year-old, or a 16-year-old out on a date."

These are actual quotes from public officials defending Roy Moore, Republican Senate candidate in Alabama. Moore is accused of initiating a sexual encounter with a 14-year-old girl when he was 32 and of pursuing several other teenage girls when he was in his 30s. Moore called these allegations “fake news.”

The Moore story is just one of a cascade of sexual abuse accusations that have become public in recent months, from candidate Donald Trump’s “grab ‘em by the pussy” comment, to Anthony Weiner’s emailing pictures of his penis to girls and women, to Harvey Weinstein’s “casting couch,” to Kevin Spacey’s molestation of young men.

How do we as journalists handle these types of stories?

It is helpful to understand that these are NOT stories about sex. They are stories about violations and crimes against girls and women, boys and men. They are stories about power and taking advantage of others who don’t have it.

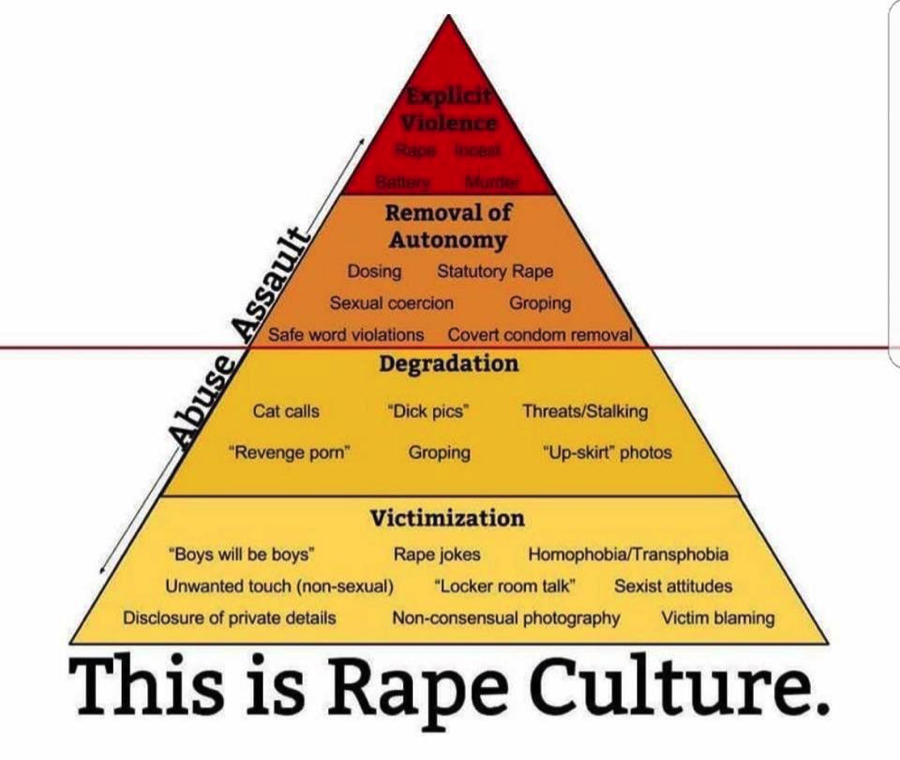

It also is helpful for journalists to understand the concept of “rape culture.” This is defined as an accepted societal belief that normalizes rape, sexual assault and sexual harassment. Rape culture blames the victim for her or his own assault or harassment and encourage myths such as “she asked for it,” “he couldn’t help himself,” and other falsehoods.

The visual below may help explain the concept. (The graphic is not perfect. The words at the top of the pyramid are “Rape,” “Incest,” “Battery,” and “Murder.”) In a nutshell, rape culture often deters victims and survivors of sexual violence from coming forward about crimes because of a fear they won’t be believed, that they will be blamed, that they will be ridiculed and/or feelings of shame.

The Associated Press Stylebook offers surprisingly little help on covering sexual abuse, beyond an entry under “privacy” that tells us not to identify people who have been sexually assaulted unless they voluntarily identify themselves. Yeah, okay.

When accusations are flying, what are our obligations as journalists?

First, we should show compassion for those who are victims or survivors. The National Sexual Violence Resource Center, a Justice Department-funded agency, finds that a majority (63 percent) of sexual violence cases never are reported to police.

Rarely are such accusations false, and we should understand it takes courage for someone who has been abused to come forward. The Sexual Violence Resource Center also finds that only about 2 percent to 7 percent of sexual violence cases are falsely reported. Therefore, as journalists, we always should be skeptical, but should keep in mind that false reports are a tiny proportion of reported cases. Some news organizations tend to jump on these false reports as big stories, which caused them to appear more prevalent than they really are. More on that in a minute.

In addition, we should focus our journalism on the bigger picture rather than dwelling on individual cases. Topics to address include:

- Why do survivors of abuse decline to report cases? The fact that many women and men have been coming forward about celebrities in the past few months points to a possible beginning of change to rape culture. It shows that when survivors bond together, they can find strength in each other.

- Why do men (and most of the perpetrators are men, even when men are the victims) engage in such behaviors?

- What about our society and culture supports the myths that victims are to blame for their own assaults? That false reports are rampant?

- Why don’t we talk more about sexual consent and what it means? This is an excellent video that helps define consent by comparing it to a cup of tea. College students love it. (Profanity warning here. There also is a “clean version” for middle and high school students.) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oQbei5JGiT8

The Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma is a stellar resource for reporting on sexual violence. For example, it advises: “Rape or sexual assault is in no way associated with normal sexual activity; trafficking in women is not to be confused with prostitution. People who have suffered sexual violence may not wish to be described as a ‘victim’ unless they choose the word themselves. Many prefer the word ‘survivor.’”

At this point, I’m guessing some journalists are asking, “What about the Rolling Stone story?” The magazine ran a story in 2014 that described a gang rape at a University of Virginia fraternity. The story was later debunked and the magazine retracted it. Rolling Stone was ordered to pay the fraternity $1.65 million.

While the Rolling Stone story had many problems, the main ones were not false accusations; they were journalistic failures. The story was based on one source, a survivor who apparently had been through a traumatic experience at some point. The reporter and editors did not check or corroborate records and sources to verify details of her story. Columbia Journalism Review took the story apart in detail, calling it “A failure that was avoidable.” CJR also published tips to avoid repeating the mistakes and noted that the incident should not deter journalists from reporting on the valid problem of campus rape.

Journalists reporting on these types of stories need to know some of the basics about sexual abuse and violence, as well as myths that continue to be perpetuated. Accurate and fair journalism is essential to changing rape culture. It also is the first step to changing sexual harassment behaviors in newsrooms.