Two Cultures Intertwined

Science and Art at LSU

There is a common misconception that art and science are two different cultures. In the 1950s, chemist and novelist C. P. Snow wrote about the divide between “two cultures,” the sciences and the humanities, and that this divide had become so stark that individuals in the sciences and individuals in the arts and the humanities could no longer communicate with one another.

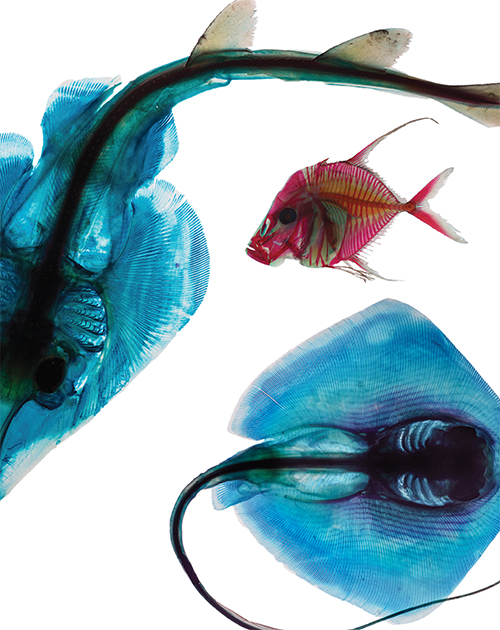

"RIP Bluntnose Stingray" from Ghosts of the Gulf series, 2014. Giclée print on handmade

Japanese rice paper.Photo Credit: Brandon Ballengée

But science and art combined provide a more holistic view of our complicated world. Today, researchers and students in the LSU College of Science and across campus are combining science and art in their personal lives, in their research projects and to engage broader audiences in science. Foster Hall, the home of the LSU Museum of Natural Science, is a building that houses both scientists and artists. College of Science undergraduate student Areen Sittichot is minoring in physical theatre and combining her love of science with artistic physical movement. Sophie Warny, associate professor in the LSU Department of Geology & Geophysics and curator in the LSU Museum of Natural Science, enlarges microscopy images of pollen grains and uses her photographs for artistic and educational purposes. These are only a few examples of science-art projects and collaborations across the LSU campus.

Prosanta Chakrabarty and a team of researchers collect specimens on a public beach

in Grande Isle during a "Crude Life" outreach event.Photo Credit: A.J. Turner

Prosanta Chakrabarty, associate professor and curator of fishes at the LSU Museum of Natural Science, recently initiated a collaboration with Brandon Ballengée, a scientist and internationally renowned artist, to explore biodiversity changes in the Gulf of Mexico. Chakrabarty brought Ballengée into his lab as a postdoctoral researcher.

“Scientists need to communicate better, and artists communicate very well,” Chakrabarty said. “I don’t know how many other scientists would take the chance to hire an artist as a postdoctoral researcher. It might seem like more work, because it involves reaching outside of your own scientific field. But I’m learning so much from this collaboration with Brandon.”

“Art is a way to communicate across boundaries; not so much to illustrate scientific concepts, but to express meaning,” Ballengée said. “I find that I have to do both art and science. If I don’t do the science, I don’t get inspired to do the art. If I don’t do the art, I don’t get inspired to do the science. The two are connected for me. When I’m doing the artwork, it inspires me to think about new methods for my scientific research, and when I’m doing science I often think about how I could turn scientific specimens into art. And I think that’s really human. None of us are totally objective – we are all both scientists and artists to some degree.”

Ballengée grew up having lots of animals, from fish to snakes to frogs and lizards. “My parents moved me into the basement because they were afraid my bedroom was going to fall through the floor because of all the aquariums I had,” Ballengée said. “But I also had a painting studio in the barn. I always needed to do both the science and the art. I also was always interested in what my animals’ environments looked like. I remember making all these artistic dioramas inside the tanks to try to figure out how to make my pets happy, or how to make them breed. So I always remember knowing I wanted to do both the science and the art.”

Ballengée completed a transdisciplinary PhD program, where he focused on amphibian biology combined with conservation through art and citizen science. Brandon says that he has seen a huge shift in terms of a greater number of programs focusing on combining science, art and communication. “The scientific community is realizing that, especially for complicated socio-ecological issues, that science doesn’t have all the tools required to cope with these challenges alone. Neither does art, or any other single discipline. But when you integrate them, and also work with a pool of local residents to see what knowledge they can bring to the table, maybe we can solve some of these really difficult issues.”

Healing the Coast with Citizen Art and Science

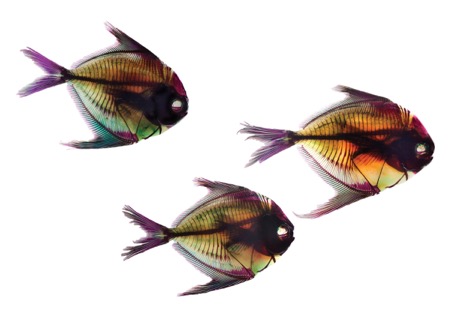

Link Morgan, undergraduate biology student with a stained fish from

"The Crude Life" exhibit.Photo Credit: Paige Jarreau

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill that started in 2010 had far-reaching impacts. The

spill affected marine life, Gulf Coast communities and even individuals internationally,

including Ballengée, who traveled to Louisiana from Quebec, Canada on several occasions

in the aftermath of the spill to work with Gulf communities, volunteer and create

art inspired by this crisis to promote awareness and engagement. “All the loss, the

loss of life, really struck me, and I wanted to do something about it,”

Ballengée said.

In the years since the spill, many researchers at LSU, including Chakrabarty and Ballengée, have been working to assess the impacts of the spill on biodiversity in the Gulf of Mexico. But an important barrier to determining the effects of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill is that many marine species collected and studied scientifically before the spill haven’t been collected since.

“We can’t really make an assessment of how these species were affected if we don’t have post-spill specimens,” said biology student Glynn O’Neill. O’Neill has been working with Chakrabarty to assess fish biodiversity and post-spill collections data from the Gulf of Mexico. “We can’t do this on our own. It needs to be a collective effort.”

“One of the frustrating things we’ve found in conducting this research is that many researchers are collecting physical specimens but not contributing the museum records and data to publicly accessible online databases like GBIF [Global Biodiversity Information Facility] and iDigBio [Integrated Digitized Biocollections,” Chakrabarty said. “At LSU all the specimens we collect go in a jar on the shelf, but we also upload data available from those specimens, such as where and when they were collected as well as genetic data, into online databases of museum records. But not all museums and researchers do this. We discovered this when Glynn helped search through databases like GBIF and iDigBio to get records of specimens collected in the Gulf of Mexico, but found that the data was limited.”

So while Glynn worked to assess pre- and post-spill biodiversity across the Gulf region via online data, Chakrabarty brought Ballengée to the team, after they met through a mutual colleague, to add citizen science and outreach components to the project to better assess biodiversity after the oil spill and raise awareness for the need for more publicly accessible data. “Brandon’s art is beautiful, and he is also a great writer,” Chakrabarty said. “We decided that we should start a project that would combine science, art and citizen science.” Thus “Crude Life” was born, a citizen art and science investigation of Gulf of Mexico biodiversity after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, funded through the National Academies Keck Futures Initiatives.

“I thought, what happens when you bring in local coastal communities that were potentially impacted by the spill, and who are also struggling with other issues, and help make them more aware of the kind of research that is needed to move forward,” Ballengée said. “Local residents and fisherman often know so much about what is happening with different species in the Gulf. They have seen the changes.” Two shrimping companies have already agreed to save bycatch for the LSU fish lab team, to help assess endemic populations post-spill. There are 14 species that the research team is looking for that haven’t been seen since the oil spill. Ballengée has given the list to volunteers including the two shrimping companies and asked them to save anything that looks like a species from that list as well as anything else unusual.

Ballengée is also bringing an art component to the project, with the goal of building a mobile Gulf of Mexico biodiversity museum and helping local residents tell their stories through visual mediums. The goal is to survey Gulf sites that were heavily oiled in order to assess whether and to what extent the endemic species have returned or recovered, and to supplement this scientific work with a mobile museum, a “portable curiosity cabinet,” that brings in physical animal specimens, bioart and cultural aspects of how the spill affected local residents and fisherman. The mobile museum will bring together a documentary film of locals’ stories about how the spill and other issues such as sea level rise have impacted the region, physical specimens collected since the spill (including fish and other endemic species such as shrimp and a deep sea roach), a microscope and slides of biological samples collected from the Gulf, and biological art pieces created by the research team, invited artists and local residents during outreach activities.

The ultimate goal is to organically foster knowledge exchange as well as a broader dialogue that could lead to empowerment and resilience of local communities. Dialogue with local residents can help researchers address complex issues and misconceptions about how marine animals such as shrimp are being affected by changing environmental conditions. For example, shrimp populations have boomed because of sinking marshes as well as decreased fishing after the oil spill, because the shrimp feed on the dead marsh grass. But what happens 20 years from now, when some wetland islands disappear completely in the face of rising sea levels? Art can be a way to start these important conversations.

“The art form is a way to communicate across these boundaries,” Ballengée said. “I think it’s very empowering for people to feel like they could be involved in the research and contribute to our portable museum.”

One intriguing component of the mobile Gulf of Mexico biodiversity museum will be a series of cleared and stained specimens – preserved fish and other marine species that have been transformed into glowing gems that are as much art as they are scientific tools.

“By having these biological specimen art projects out there, people get interested and become aware of Louisiana’s incredible biodiversity,” said undergraduate biology student Link Morgan. Link is a curatorial assistant in the LSU Museum of Natural Science. He is helping with the Crude Life project with Chakrabarty and Ballengée. “People start asking questions, and we love that. As scientists we are asking questions all the time.”

Individuals and organizations who want to get involved with the Crude Life can contact Brandon through his website, brandonballengee.com or at bballengee@lsu.edu. Citizens and kids who attend Crude Life events along the Gulf can help Chakrabarty and Ballengée’s team collect specimens, learn about the process of clearing and staining specimens for morphological analysis, and create art surrounding their experiences. Shrimpers and other fishing organizations can also get involved by contacting Ballengée about saving bycatch for identification of endemic species. Ballengée has a handout of 15 marine species that haven’t been seen since the spill, that fisherman and citizens can be on the lookout for.

Fish Gems, for Science and Outreach

Link learned the tedious, time-consuming and artistic process of clearing and staining. This is the now dying art of taking a biological specimen preserved in formalin, making its soft tissues transparent and staining its cartilage and bones with vibrant blue and red dyes. While other technologies are now readily available for imaging the bones and cartilage of fish and other animals, cleared and stained specimens are immensely useful for studying of morphology in three dimensions. Two fish may look the same on the outside, but their bone morphology may reveal a very different picture about how closely related they are.

“When you look at a fish, you just see scales. But when you look at a cleared and stained fish, you can see the details of the bones and cartilage,” Link said, pointing to the delicate ribcage and skull of a cleared and stained Madtom catfish in the basement of Foster hall. “To me, this reminds me of our rib cages and our skull, and that makes me draw a personal connection with this fish.”

“When I first saw a cleared and stained specimen, I thought ‘wow, that’s amazing. I have to figure out how to do that,” Ballengée said. His PhD advisor later taught him this aesthetically compelling scientific procedure, and Ballengée is now famous for his photography of deformed frog specimens he cleared and stained himself. The procedure is also useful for the Crude Life project. Some new research suggests that some marine species affected by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill had abnormal bone morphology, something that Ballengée is now investigating partly through clearing and staining.

For fish specimens, the process starts with taking the scales off of a preserved fish, drying the specimen out in ethanol, removing the soft tissues with a solution of trypsin (an enzyme that removes protein), and then soaking the specimen in a series of colorful dyes or stains for several days. The final cleared and stained specimens are placed into oil for viewing. The whole process takes over a month to complete. Link is one of the only researchers at LSU, and very likely the only undergraduate researcher, who knows and regularly practices the clearing and staining process.

“A process for clearing soft tissue and staining specific tissues in biological specimens was first published in 1927,” Link said. “But it wouldn’t be recognizable until 1977, when this specific method was developed. This method was useful because it works on specimens that had already been preserved. We have thousands upon thousands of preserved specimens here at the LSU Museum of Natural Science. With this process, you can take one of those, whether it be from 2012 or from 1951, and put it through this process to get a cleared and stained specimen.”

“The most lengthy step is the trypsin clearing step,” Link said. “Trypsin is an enzyme, and it’s a pretty cool enzyme because it’s found in a lot of vertebrates’ digestive systems. The trypsin removes all the proteins from the specimens, and leaves only collagen. Collagen is the stuff that people want to keep in their faces and that is the focus of a lot of beauty products,” Link laughed.

Link has cleared and stained six specimens so far, including two long-eared sunfish, two Madtom catfish and two topminnows – all fish found in Louisiana.

“I really enjoy the clearing and staining process,” Link said. “It’s a labor of love. Like painting, you can’t rush the process and what you start with isn’t necessarily what you end up with. I’m a perfectionist, and I like the final products to look as pretty as possible.” By pretty, Link means a specimen that is completely clear except for perfectly stained blue cartilage and red bones – like a beautiful, three dimensional, colorful x-ray image.

“Honestly, CT and MRI scans are getting so fast that clearing and staining might be a dying art, but it’s such a beautiful way to look at biological specimens, and it’s still very useful,” Chakrabarty said.

“Research is its own art-form,” Link said. “It takes time, and there are no guaranteed meaningful results. Usually you find something, whether it’s exactly what you thought you’d find or something totally different. But just like a painting, scientific data could mean one thing to us, but to different researchers in the future, it might mean something totally different.”

The Heart and Movement of Science

Areen Sittichot, a biological sciences student at LSU, wears a "biological cell" costume

during an aerial silks performance created for the Edinburgh Festival Fringe.Photo Credit: Andy Phillipson

Other faculty and students in the College of Science are exploring science-art connections across campus. For Areen Sittichot, or “Reeny”, science is not just a series of facts to be learned. Science is the physics of movement, it’s social, it’s emotional, it’s human.

Reeny has personal connections with science, sports and physical art. She was an accomplished gymnast before she joined the LSU College of Science in 2013. Her 10-year gymnastics career ended when she injured her back in high school, but her injury and the sports medicine practitioners who helped her through her injury inspired her to pursue a career in medicine, starting with a biology degree at LSU. She is currently a senior in the premed program of study.

“I heard about the aerial silks class at LSU through word of mouth,” Reeny said. “I auditioned and Nick Erickson let me in the class.” Erickson is an associate professor of movement and associate head of M.F.A. Acting in the LSU College of Music & Dramatic Arts. “I immediately fell in love with this artistic sport. My background in gymnastics helped – I had the upper body strength and endurance that are often difficult for other aerial students to gain in the beginning of learning aerials. But aerial also combines grace and dance, which is what I always struggled with in gymnastics. So it was something new, yet familiar.”

Reeny excelled in her first aerial silks class, and continued to take other aerial and physical theatre classes. She had only been practicing aerial arts for a year when Erickson invited her to join a study abroad program and aerial performance in the summer of 2016. The program brought together two theatre courses, THTR 3800: Theatre Internship and THTR 4029: Special Topics in Stage Movement, for which students had to take photos, film videos and write about cultural aspects of the countries they visited, including France and Scotland, as well as evaluate and reflect on the various aspects of putting together a physical theatre show, from physical performance to costume design and marketing the show. The program culminated with a performance at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in Scotland called Savage/Love, based on Sam Shepard and Joseph Chaikin's play by the same name.

“I thought it would be fun, but I said no at first,” Reeny said. “I was studying for the MCAT that summer and fall semester. I didn’t think going to Europe to perform would work logistically or practically with my plans ands goals at the time.” But in the end, Reeny decided to go for it. She committed to the summer study abroad and started rehearsing for Savage/Love. Rehearsals lasted 5 hours a day during the summer, and all the while Reeny studied another 5 hours every day for her MCAT (Medical College Admission Test).

But studying for the MCAT wasn’t the only way that Reeny combined science with her theatre study abroad and aerial arts performance experiences. The aerial show Savage/Love also brought science and art together in ways that made Reeny look at science in new ways.

“Nick describes Savage/Love as the ins and outs of real and imagined moments of love,” Reeny said. “It was a crazy compilation of a dozen poems that we performed piece by piece, and science and technology that brought our performances of the poems to life.”

For one piece, “Watching the Sleeping Lovers,” an overhead projection of the stage appeared on a screen at the back of the stage while Reeny and other performers danced on the ground in a choreographed movement representing a sleep-like state.

“The projections were my favorite part of the show, because there was so much science going on through the images,” Reeny said. “The projected images and videos showed cells moving, neurons firing in the brain, an anatomically correct heart beating, a nervous system, veins and arteries with flowing blood. Even our costumes incorporated the biological system and its chemicals. My costume had microscopic images of cells covering it – the images reminded me of gram staining [a common technique used to differentiate two large groups of bacteria based on their different cell wall constituents].” All of the projections and images of biological systems brought science and anatomy into a performance about how falling in love is not just an emotional experience, but also one that is physiological and neurological.

“There is a notion from Descartes that the mind and body are separate entities, one a reflection of the soul, the other a vessel to temporarily house the other. This separation is disappearing with modern science,” Erickson said. “Nerves, once thought separate from the immune system, are found there. The brain speaks to all systems of the body. Aerial practice is also a form of physical performance that unifies mind and body. Metaphorically, classical mechanics crashes into quantum mechanics when a flawless aerial solo unites the performer with the observer. Performer, vision and viewer come together as wishes are illuminated, dreams are fulfilled, and beauty and grace are embodied. Quantum entanglement could very well apply to live performance in a grand metaphor.”

Reeny had a special connection to the scientific images that pervaded the Savage/Love show, as well as the physics of the aerial movement, because of her background in the sciences. “I feel like I had an advantage in some ways,” Reeny said. “While spinning or moving in the air, I understand the forces of gravity and the implications of the conservation of angular momentum in a different light than everyone else. There is a huge advantage even in aerial arts to knowing how science works.”

But exploring the artistic side of the Savage/Love performance was new for Reeny. It made her see science in a new light.

“It was a very different experience, prioritizing this movement and art in my life for the summer,” Reeny said. “At the surface level, movement is a great form of exercise and relief from the stresses of preparing for medical school. But at one point in rehearsing for Savage/Love and seeing the scientific projections behind us, I just had to stop for a moment to think how cool this is, that our bodies can do these things, flow through the silks in the air. Everything in our bodies, down to the smallest cells and even individual atoms, have to function correctly and contribute to a giant system in order for us to move the way we do. I go to my science classes and we talk about facts, but when performing aerial, I have to connect emotion to what I know scientifically about the human body and the physics of movement.”

When she first started rehearsing for Savage/Love, Reeny said her tendency was to make lists and go through the training and movements for the pieces methodically, as if she were conducting a scientific experiment. But the other artists she was working with seemed to process the rehearsal much different – more emotionally.

“Performers really process their emotions before making a move, or making a decision,”

Reeny said. “Rehearsals for

Savage/Love changed from day to day based on how everyone was feeling, and at first

that drove me crazy. It scared me, I was a wreck. And then performing a show in a

foreign country was completely unpredictable.”

Reeny said that her experiences in a group aerial art performance have taught her patience and how to deal with things out of her control, lessons she can bring back to her scientific training.

“Scientific research is also unpredictable in some ways,” Reeny said. “In my ecology lab this semester, we had planned to set up plots in the swamp, but because of flooding our original plots were ruined and now we have to do something different. That part of science is relatable to putting together an artistic performance. And scientists have to collaborate in their research, just as the performers in our group had to work together to bring Savage/Love to life. Scientists have to build on other scientists’ work, just as artists build on other artists’ work.”

Reeny plans to continue to combine science and performance arts. She graduated in May, 2017 with a degree in biology as well as a minor in physical theatre. She plans to take a gap year before she enrolls in medical school, during which she might travel on medical mission trips and continue her development in circus arts. Reeny has always enjoyed traveling – her family is from Thailand and last summer she had the opportunity to shadow doctors and gain valuable medical experiences at Pranangklao Hospital for three weeks, so she may return there during her gap year. Reeny is also the fundraising chair for the LSU chapter of Global Brigades, an international non-profit that empowers communities to meet their health and economic goals through university volunteers and local teams.

“Doctor by day, circus performer by night – that would be the life,” Reeny joked. But more seriously, Reeny has found that aerial performance and physical movement have inspired her medical interest in the human body, and that vice versa her in-depth understanding of physics and body mechanics have inspired her pursuit of physical performance. Whether it’s in her science or aerial arts, Reeny inspires others to pursue their dreams.

Reaching Out to Artists

“There are a lot of scientists who are excited to work with artists, but there is also a lot of ignorance about how complicated the arts are at this moment in history,” Ballengée said. “It is important that scientists try to understand just how rich and complex the arts have developed in recent decades, and not just see them as pretty pictures. Artists should not be expected to just illustrate the concepts of scientists’ discoveries. For a functional art-science collaboration both parties need to respect and have a basic understanding of the field of the other.”

Collaborations between artists and scientists have resulted in a wide range of innovative projects, from a zero gravity dance performance, to music made with electromagnetic waves, to tissue engineered sculptures, to phytoremediation sculpting of toxic landfills. The list goes on. “Many artists have crossed the disciplinary divide and made important scientific discoveries, and likewise some scientists are also now making great art,” Ballengée said.

Ballengée encourages scientists looking for artists to collaborate with to stop by their campus art department, a local art center or a gallery and introduce themselves. Other resources for science and art collaborations can be found through the Cultural Programs of the National Academy of Sciences (USA), The MIT Center for Art, Science & Technology (USA), Le Laboratoire Cambridge (USA), Arts Catalyst (UK), SymbioticA (Australia), Artists in Labs (Switzerland), Leonardo/The International Society for the Arts, Sciences and Technology (USA), Incubator (Canada), Ectopia (Portugal), and the Finnish Society of Bioart (Finland).

“Do a little online research. There are very many art-science resources and programs happening all over,” Ballengée said. Chakrabarty and Ballengée are also beginning to work on organizing a future LSU Art-Science Symposium.